Suppose we have two parallel polygonal faces with a non-zero distance between such that, for some pairing of vertices, every consecutive pair of edges connecting the paired vertices are coplanar. It follows that the faces joining the two given parallel polygonal faces are quadrilaterals. At first, it might not appear that this is a sufficient condition to assert that the shape thus described is a frustum of a slanted pyramid. In this post I proceed to prove that it is. For the volume formula of a frustum of a pyramid (slanted or otherwise), see

this previous post of mine.

I term the parallel polygonal faces the end faces and the other faces as the side faces.

Proposition 1 (Transitivity of Parallel Lines).

- Let P be a plane and L a line parallel with P. Every line parallel with L is also parallel with P.

- Let L, M, N be lines. Then, if L is parallel with M and M with N, then L is parallel with N.

Proposition 2. The corresponding edges of the polygons are parallel with each other.

|

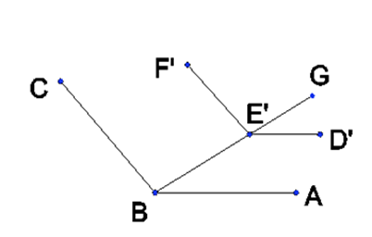

| Fig. 1. Partial drawing of two parallel planes. AC is the "bottom edge" and BD is the "top edge". AB and CD are "side edges". Consecutive side edges are coplanar with each other. |

Proof: Assume without limitation that the faces are parallel with the horizontal plane. Since the faces are parallel, the edges do not change in proximity vertically. Consider any two consecutive edges AB and CD joining the two end faces with corresponding vertices A with B and C with D. Draw line EF with E on line AC (edge of bottom face) and F on BD (edge of top face; extend BD as necessary) such that EF is perpendicular to AC. EF is coincident with the plane of quadrilateral ABDC and so is coplanar with all of its edges.

|

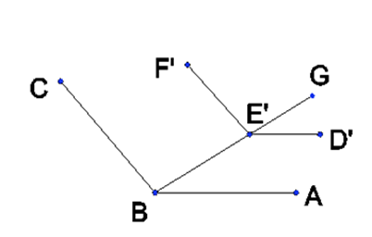

| Fig. 2. We show the construction of B'D' as a line which is coincident with BD, but this is not given as a condition in the construction. That is to be proved. At construction we take neither parallelness nor coincidence with BD for granted. Because it is the same distance from AC as the point F, however, we do know there is at least an intersection between B'D' and BD at F. |

Let B' and D' be points such that AB' and CD' are of length(EF), coincident with the plane of quadrilateral ABDC, and perpendicular to AC. Then AB' and CD' are parallel.

If you want to go crazy with the details to see that B'D' is parallel with AC, see the parenthetical section below. I obviously did want to go crazy. Normal people can skip ahead.

(By side-angle-side, triangle AB'C is congruent with triangle CD'A. Thus,

Also, since the non-right angles of a right triangle sum to 90°,

Thus, triangles B'AD' and D'CB' are congruent by side-angle-side. Hence,

By alternating interior angles,

Since the angles of a triangle sum to 180°,

Hence, angle B'D'C is a right angle. By a similar argument, angle D'B'A is a right angle and so quadrilateral AB'D'C is a rectangle and thus B'D' is parallel with AC. Since F is length(EF) away from AC, in the same plane as quadrilateral AB'D'C, on the same side of AC, it is on line B'D'.)

Thus, triangles B'AD' and D'CB' are congruent by side-angle-side. Hence,

By alternating interior angles,

Since the angles of a triangle sum to 180°,

Hence, angle B'D'C is a right angle. By a similar argument, angle D'B'A is a right angle and so quadrilateral AB'D'C is a rectangle and thus B'D' is parallel with AC. Since F is length(EF) away from AC, in the same plane as quadrilateral AB'D'C, on the same side of AC, it is on line B'D'.)

|

| Fig. 3. The shape we are discussing doesn't really look like this, but how do we know it doesn't look like this? How do we know Fig. 2. isn't the one that's wrong? See rest of argument below. |

Assume that lines BD and B'D' are not coincident. Both are coincident with a common plane and so are coplanar. Since quadrilateral ABDC is on an angle from horizontal and BD and B'D' are not coincident, there is some point, P, on B'D' which is below BD. But point F is coincident with both BD and B'D'. Since BD is parallel with horizontal (it is part of a polygonal face which is horizontal), and B'D' has at a point on and a point below BD (points F and P, respectively), B'D' is not parallel with the horizontal plane. But, since AC is parallel with the horizontal plane, the parallel line B'D' must be parallel with the horizontal plane (Proposition 1), which is a contradiction. Thus our (limiting) assumption is wrong and lines BD and B'D' are coincident. It follows that BD is parallel with AC.■

Corollary 1. The walls of the prism are trapezoidal.

Proof: The corresponding edges of the end faces are parallel.■

Corollary 2. Every cross-section of the prism, parallel with the end faces, has corresponding edges parallel with the end faces.

Proof: Fix any cross-section parallel with the end faces and observe that the side edges are intersected by this cross-section so as to produce a polygonal face, whose vertices and edges correspond with the bottom face in the same way the top face did in the proof of Proposition 2. The same argument, therefore, applies.■

Proposition 3. The top and bottom faces are similar shapes.

Proof: It suffices to show that the interior angles at each pair of corresponding vertices are equal. Let

A,

B, and

C be consecutive vertices of the bottom polygon and

D,

E, and

F be the corresponding vertices of the top polygon, respectively. By Proposition 2,

DE is parallel with

AB and

EF is parallel with

BC. There exists vertices

D’,

E’, and

F’ which are translated vertically from the top polygonal face down to the plane of the bottom polygon. By this we obtain lines

D’E’ and

E’F’, in the plane of the bottom polygon which are parallel with

DE and

EF, respectively. By Proposition 1,

D’E’ is parallel with

AB and

E’F’ is parallel with

BC. Draw a line through

B and

E’ to some point beyond

E’, say,

G (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

AB ||

D’E’ and

BC ||

E’F’.

Then we have corresponding angles ABE' = D'E'G and CBE' = F'E'G. Thus, ABC = D'E'F'. We take for granted that the translation of

DEF to

D’E’F’ did not alter the angle between the lines and so we have our result.■

Corollary 3. The cross-section taken parallel with the end faces is everywhere similar to the ends.

Proof: By observing that the parallel cross-section intersects the trapezoidal walls of the prism so as to produce lines which are parallel to the base and top (Corollary 2), the argument applied for Proposition 3 applies here as well.■

Proposition 4. The lines extended from the side edges intersect at a common point (the apex).

Proof: Consider three consecutive vertices on the base A, B, and C, and corresponding vertices D, E, and F on an arbitrary parallel cutting plane parallel with ABC. By corollary 3,

Since AD and BE are coplanar, they intersect at some point P. Similarly, BE and CF intersect at some point Q. Assume that P ≠ Q. Take a section parallel to the base through P and label the vertices of the section which correspond to A, B, and C as D, E, and F and observe that the above proportion equation still follows from corollary 3. Also, D = E = P and so line segment DE = 0. However, since P ≠ Q, line segment EF ≠ 0, which contradicts the proportion above. Therefore, our assumption that P ≠ Q is wrong and we have P = Q. By the principle of mathematical induction, the proposition follows. [Finding P is (i) 2 in S and establishing P = Q is (ii) the inductive step. 1 in S is either automatic or ill-defined I suppose, but irrelevant anyway.]■

The shape we have considered in this post is a frustum of a (possibly slanted) pyramid by proposition 4.

We conclude by noting that the argument for determining the volume of the frustum of a pyramid does not impose a condition that requires the top face to be centered over the bottom face. A slant does not alter the argument and therefore the result is the same. Note, of course, that the height must be measured perpendicularly to the end faces. It should be noted that we have not dealt in this post with the relationship between the cross-sectional area and the height, which relationship is needed in order to establish the volume formula.

Such proof involves 1) similar triangles, using the height of the apex as a reference, and 2) the relationship between linear dimensions and the area(s) they pertain to. Assurance of the existence of a proper apex is the critical component addressed in this post.

Thanks to one of my readers for the question

at the end of a previous post that led to this post.